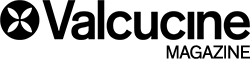

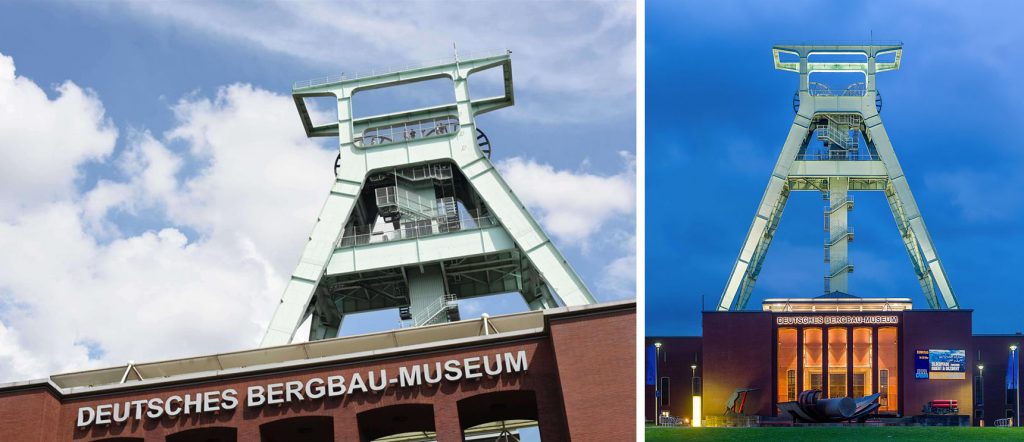

“In my Ruhr sustainability has a steel heart”

Salvatore Giannella interviews German art historian, Roland Guenter.

Dear Roland, I want to start our journey across the international community of architects, interior designers and scholars of various subjects from you, a German art historian. My aim is to shed light on the evanescent path of sustainable development with practical examples and advice.

I am curious about your choice (we know each other so well that it's difficult for me to address you formally). Why am I honoured to be the first stop in your eco-technological journey?

I got this idea from the latest edition of the National Geographic Traveler magazine. In the cover story, the editorial staff of the various international editions listed the 25 most exciting places to visit on Earth in 2022, and divided them up into 5 categories: Adventure, Culture, Nature, Families and – more to the point – Sustainability. For the latter category, which was made famous by the Bruntland Commission of the United Nations on 20th March 1987, the choice fell on the region you live in: the Ruhr valley, in North Rhine-Westphalia. This was the official reason: “This region of Germany is currently changing the destination of use of its coal and steel industrial sites into parks and cultural areas”. My choice was also backed up by the European Union workshop held on 16th October 2021, here in Essen, on the sustainable management of industrial sites in urban development. You, Roland, have been a pioneer in saving industrial sites from demolition and in virtuously converting them.

Indeed, in my long life (I was born in 1936) I have received many acknowledgements in Germany and even in Italy: I remember the Rotondi Award for the “saviours of art” given to me in Montefeltro, in the Le Marche region, as stimulator of the restoration of the beauty, poetry, history and culture of landscapes.

Photo credit: Hans Blossey

In fact, these words are rarely spoken by those who, especially in entrepreneurial circles, preach about the importance of sustainability. Indeed, when talking about an ecological transition, they focus on two key concepts: reducing the impact on the environment and shouldering production and consumption issues.

And yet, you in Italy, ideally the first cultural power on the planet, have the right ingredients to create a winning combination capable of making you leaders in sustainable economical activities and in planning a future that is friendly instead of threatening. I can say this because I know Italy well; I call it my second home. My wife, Janne, and I feel Italian by adoption; we had a study in Anghiari, in Valtiberina in Tuscany, for many years and we fostered the conversion of Sulcis, of Bagnoli and of Taranto itself, for years as well.

Let's go ahead with your advice for Italians, based on your experience in the Ruhr region.

When converting a building, a territory or an industry, its historical heritage must always be kept well in mind. It's nice to dress the future in ancient robes: you Italians – unlike other countries, like my Germany, that tend to destroy their history – have had these robes for two thousand years. When producing coal and steel stopped being profitable, many people here wanted to demolish everything, raze it to the ground, like they do in other places. My friends and I said no: this heritage of industrial archaeology is a piece of our history and of our identity; it's an industrial culture site whose dignity should be acknowledged. It's a heritage that should be redeveloped with a modern function. Farsighted administrators and entrepreneurs put their trust in us. In 1989, the “Land”, i.e. the Region, purchased the mining basin area with its abandoned buildings. A foundation consisting of institutional and private representatives was set up and it became the steering committee of the Conversion Operation, collecting the first 600 million Euro.

Photo credit: Lukassek / Shutterstock.com

Let's make some practical examples.

Very near my home, in Oberhausen a Gasometer, built in 1929 to store coke oven gas, had been operating for a long time. When we were about to start the conversion, almost everyone wanted to get rid of that steel giant, which was just seen as an ugly container. I wrote, and proved, that it could be converted into a marvellous theatre or museum. That former Gasometer has now become one of the most original exhibition spaces in Europe, together with the former Zollverein coal mine in Essen, one the UNESCO world heritage sites, a symbol of conversion excellence for the entire region.

Photo credit: Thomas Machoczek

The former Gasometer, the ex coal mine (which now houses an outdoor swimming pool, an ice-skating rink and pathways for walks) as well as the former blast furnace, the ex extraction towers which are now used to train mountain climbers of the German Alpine Club, former slag heaps which have become panoramic spots featuring artistic attractions. In fact, along the industrial heritage route, 400 km from Duisburg, in Hamm and Hagen, there are 54 extraordinary pieces of evidence of the Ruhr's working past and present. In the five leading towns – Duisburg, Oberhausen, Essen, Dortmund and Bochum – as well as in the other 54 centres of the region scattered over 4535 square km, thousands of old industrial sites have contributed to creating the densest concentration of museums (about 200) in the world. Bochum – that used to be the town with the most mines – is now the one with the greatest number of theatres. More than twenty thousand jobs have been created, many of which have been given to the children and the grandchildren of miners and labourers.

We are talking about transforming the most industrialised region of the world: more than 400 thousand labourers worked here in the first half of the 20th century. It was the site of the German industrial revolution which powered the luxury trains of the Belle époque and made the middle-class of Central Europe prosperous. This conversion into a green region, which became the leader of cultural tourism, was made possible by respecting its industrial heritage and continuing to honour it. If our industrial site had been destroyed, our territory would now be a desolate, desert land. Instead, yesterday's values were added to today's, transforming the region into an enormous theatre (containing more than 120 arenas) which – since 2010 when it became the cultural capital of Europe and achieved a record attendance of 17 million people – has been attracting the same number of visitors (taking the pandemic into account) as your Pompei.

Photo credit: H. Grebe | Photo credit: Tuxyso

Visitors with a high degree of curiosity and of mobility (and who can spend) driven by a powerful incentive, i.e. their longing for significant experiences which are a fundamental means of acquiring knowledge and of building a reputation.

In my opinion, Goethe represents this type of traveller: not a genius but a man driven by his insatiable curiosity. This consideration refers to the administrators of the territory (who should be properly educated in this regard by means of lots of books and meetings) but it should also involve entrepreneurs attentive to innovation and interested in sustainability, at the helm of businesses with a historical heritage that can even become an important factor on the balance sheet of our post-industrial age.

Books and encounters, wishes. Which books? Which people?

The best books are those that talk about local, in particular industrial, history, and I have had the honour to write many on this topic. I dedicated my most recent book to the centenary of Bauhaus, the school of architecture, art and design founded by Walter Gropius, which was also the breeding ground of innovators such as the artists Paul Klee and Wassily Kandiskij. You can read it on Werkbund-initiativ.de. The encounters took place with experts in the field of culture and talented visionaries: people like Karl Ganser, geographer and town planner, the manager of some of the conversion projects in the Ruhr, who started up circular economy involving land and energy consumptions, building heritage and water management. I dedicated a biography to him. But I would add poets to these experts.

Poets? Putting poets and entrepreneurs interested in making a profit together sounds complicated to me.

Yes, you've understood correctly: to set up a framework for a sustainable future we must listen to our poets. I know this from personal experience: I took my young university students on training trips in Italy for years. I used to take them to Pennabilli, in the province of Rimini, almost 1,400 km from here, to listen to the advice of Tonino Guerra.

I know, I know….I was once the direct witness of a significant lesson in the Town Hall, held by that beloved friend and master in the beloved village in Romagna.

There that great poet and scriptwriter, favoured by Fellini and Antonioni and by many other famous film directors, enriched Valmarecchia with many poetic inventions that were as inexpensive as they were fascinating: one of the most representative is the small but evocative museum exhibiting just one picture, and the vegetable garden of forgotten fruits. Tonino's ideas have also been important in converting the Ruhr, to the extent that there is a park named after him along a reclaimed waterway, with a bench enriched by a statue and by a totem that tells his stories to passers-by. In his Romagna, Tonino continuously produced creative ideas, dreams that have become a network of abodes for the soul, also thanks to his brilliant and practical collaborator, Gianni Giannini, and to the many top-quality craftsmen he attracted.

He understood that the secret to success was, and still is, to bring together skilled and visionary local government officials (such as Heinz Dieter Klink, governor of the Ruhr from 2005 to 2011, while I was member of the Deutscher Werkbund, the German Association of Craftsmen, one who used to say: “Although the majority and the opposition have different visions, they have always agreed on the future of the region”), together with managers and civil servants who are ready to give up their own limited power and have not subsided into a sterile turmoil of paperwork, that same paperwork that lead to the unfair condemnation of the Riace model to alleviate the refugee emergency in Europe. It is also important to involve local development officers who, in the end, are also responsible for helping central government assign funds.

In my blog, the poet Franco Arminio calls him the town's “coach”: a person sent to a clearly-defined territory made up of three or four villages at the most, who stays there for three years, settling there and talking to the people who work, or could work, on the territory every day.

Precisely. Lastly, the skilled and practical hands of professionals, craftsmen-artists who used to come out of Schools of Arts and Crafts, trainers of the imagination, to whom we should once again hand over a future worthy of their past. In this case too, Italy could send an important message to Europe and to the whole world.

This interview is part of a series that will be contained in Salvatore Giannella's (writer and journalist, former director of L'Europeo and Airone) new book, which will be available in 2022, in collaboration with Valcucine.

Photo credit cover: Jakob Studnar

LATEST POSTS